The Claude Debussy First Arabesque, composed in 1888 in the key of E major, is like an arabesque, an ornamental design consisting of intertwined flowing lines. Yet there’s more in the music then its contours. The First Arabesque has strong antecedents in Bach.

An Instructive Video from Stephen Malinowski

In his video of the Debussy First Arabesque, Stephen Malinowski has created an effect that is both ethereal and vibrant, through a shimmering sound and his tasteful use of rubato. Each bubble popping on the screen corresponds to a note in the music, while the bubbles’ colors represent voices: purple for the bass, light gold for alto, for example. The video makes manifest how a single line in the score can actually consists of two or even more voices—a treble line, for example, divides into a soprano voice with a rippling alto accompaniment. Here then is a visual example of how Debussy was influenced by Bach’s purity and counterpoint.

In addition, Malinowski chose to portray the melodic soprano line in two colors, a light blue and a lavender, alternating the two. “Debussy’s development of the melodic line uses repetition,” he explains, and the repeated part is “either longer (by extending the melodic idea) or shorter (by truncating it). I alternate colors to make this more obvious.” For example, the very first melodic phrase in the music, represented by light blue, is just three notes. When the melodic phrase repeats—now shown in lavender—Debussy has extended it to seven notes. The video is part of a larger body of work by Malinowski for his Music Animation Machine.

The Dreaded Three against Two in the Debussy First Arabesque

As a student of adult piano lessons, I decided to study this music to master the technique of triplets in the right hand versus eighth notes in the left. Previously, when this pattern cropped up, I played it with my eyes closed, as though cowering on an amusement park ride while passing underneath the waterfall, hoping not to get too wet with my incompetence. But in the Debussy First Arabesque, I had to master four consecutive triplets against a string of eighth notes. This is the music’s most well-known motif, the right hand tumbling down the keyboard like a waterfall (a real one, not a fake, amusement park one), while the left hand flows upstream to meet it. I figured if I could master the three against two problem in the Debussy Arabesque, I could execute the technique with my eyes open.

Here’s the process that my piano teacher recommended:

- Learn the two hands separately very well.

- Play the right hand slowly, and in the left hand, only play those eighth notes that match up with the beginning of each triplet.

- Again play the right hand slowly, in perfect time, and add in the first eighth note that does not match with a triplet note in the right; play to the end of the phrase.

- Slowly add in the few remaining left hand notes that do not coincide with a triplet, making sure to keep the right hand timing measured. Play through to the end of the phrase.

Much to my surprise and delight, this process worked, and in a few weeks I was able to play the two hands together at tempo. Although I did not end up learning this music well enough to perform it, I still enjoy rippling those two measures of the three against two.

Amateur Pianist Toshiko Noshino Interprets the Music

I’ve found it comfortable to play the Debussy First Arabesque because it is easy to imagine an idea for each section of the piece. While I play, I see water flowing or birds taking off into the air; other times I see a green field. Almost the whole time I am imagining some sort of tableau.

Sometimes a teacher will give me a lot of suggestions on a piece, and often I take their suggestions and then make them my own. In this case, my teacher suggested that in the opening, the right hand is a kind of melody and to play it with more emphasis than the left. Of course I tried to make the right hand have a bigger sound than the left, but I ended up compromising to create less difference between the two.

When I studied Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude, it was more about technique. Of course for the Debussy First Arabesque I need technique, but it’s more about interpretation and feeling the music. With this piece, I am able to express myself more.

Advice from a Contemporary and Friend of Debussy

The Debussy First Arabesque “is essentially contrapuntal in texture,” says E. Robert Schmitz, a pianist and friend of Debussy. In The Piano Works of Claude Debussy (Dover, 1966), Schmitz outlines how in measure six—the same measure in which I tackled the devilish three against two—the music has “two voices progressing in alternation and united as a single melody.” The music here is reminiscent of Bach in the Well-Tempered Clavier.

Schmitz also zeroes in on the poetic middle section (which occurs from measures 29 to 46). “Note that the music has become more emotional,” he says. “It is rich in abandon, swaying impulses, tenderness, and fantasy.” In order to draw out this effect, he recommends paying close attention to the appoggiaturas, taking advantage of those moments when non-chordal notes loosen their tension and resolve.

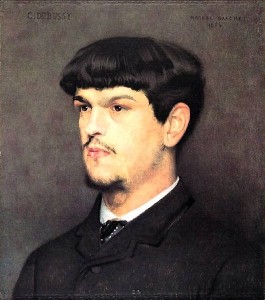

The Ironic Contrast between Debussy’s Person and His Music

“Physically, Debussy was very unlike the willowy and soulful-looking aesthete fondly imagined by so many of the young women who with all too faulty fingers were wont to essay the First Arabesque and the Jardins sous la pluie,” says Alfredo Casella, a pianist and conductor who appears in Roger Nichol’s Debussy Remembered (Amadeus Press, 1992). Although perhaps captive to the social stereotypes of his times—he penned these remarks in 1933—Casella echoes the contrast between Debussy’s appearance and his music that so many biographers cannot resist. Casella continues: “He was of middle height, and was thick-set and sturdy. The head was a strange one: the enormous forehead bulged forwards, while there seemed something missing at the back of the huge skull…. As always with artists of the finer sort, the hands were most beautiful.”

The Debussy First Arabesque in the Context of the Composer’s Body of Work

Debussy’s “work has a texture—transparent, glowing, vaguely modal, exotic, unerringly precise—that is one of the most original in music,” waxes Harold C. Schonberg, in his classic, The Lives of the Great Composers. Debussy composed the First Arabesque in 1888, early on in his career, yet the composition hints at his later, mature piano works. Schonberg declares that it is critical to understand that Debussy thought in a new manner.

In this archetypal passage from one of his letters, Debussy writes: “I am more and more convinced that music, by its very nature, cannot be cast into a traditional and fixed form. It is made up of colors and rhythms. The rest is a lot of humbug invented by frigid imbeciles riding on the backs of the Masters—who, for the most part, wrote almost nothing but period music,” he blusters in his antagonistic style. But then he concludes, revealingly, “Bach alone has an idea of the truth.”

This article on Debussey Amplified is now lacking the video, at least on my screen, and the one on utube now has a black background making it hard to see. Is this no longer available in the light-background version I first saw?

Cathron, thank you for alerting us to this problem. The video is now fixed!

My piano teacher just gave this piece to me after still struggeling a bit with Chopins polyrythm in Fantaisie Impromptu. So, it is alsi an exercise in polyrythms.

The animation by Stefen Malinowski is fantastic. In fact, it helps understanding this piece. Great work! (Only, the video streaming is interrupting from time to time on my machine — which is a technical issue.)